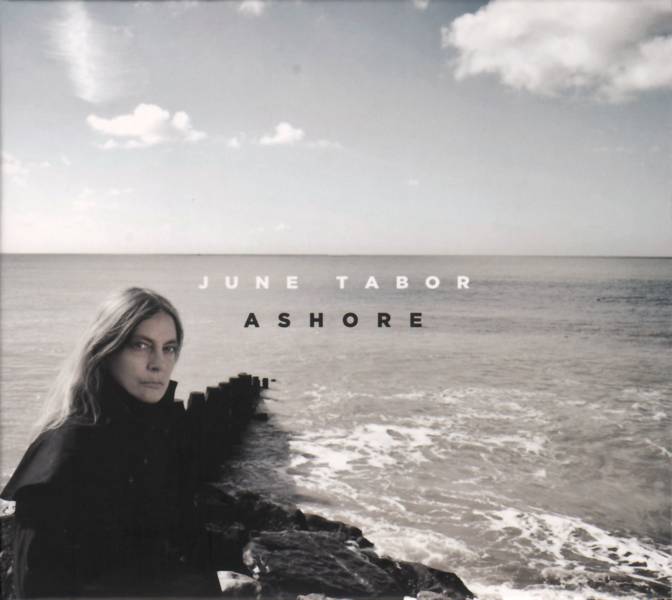

In early 2011 I had the privilege of interviewing the singer June Tabor (b. 1947) for a now-defunct music magazine. Since then she has continued her collaborations with Oysterband and as part of the trio project Quercus. But Ashore, which we discuss here, remains to date her last solo album…

********

“I might be under a bush or making marmalade,” says the voice at the other end, explaining why she doesn’t always hear the telephone. Luckily, June Tabor, gardener, marmalade-maker – and one of the greatest living interpreters of English song – is engaged in neither activity when I call to ask about her new album, Ashore.

The album, her thirteenth as a solo artist, has its origins in the seventieth birthday celebrations for Topic Records, the label that June has been with throughout her career. Tony Engle of Topic invited her to do a concert at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall and gave her a free hand in the programme. “I like when putting together a concert to bring together songs that tell a story, trace some kind of storyline, songs that are connected in some way, possibly by subject matter, irrespective of where they might come from,” June explains.

She’d long been thinking about a concert in themed sections on the relationship between the British people and the sea. “That doesn’t mean, as some people seem to think, sea shanties. That’s just a very small part of it. There’s a huge breadth of material which has the sea as its subject matter or its inspiration, both in the tradition and in the hands of modern writers. And if you juxtapose things that haven’t previously been put together but which still have this connecting thread, and in this particular case the sea, it’s amazing what pictures and images, what passions you can stir up amongst us all, performers and audience.”

After the concert, once she’d got over the “abject terror of doing a whole lot of new stuff in one go”, she realised she had the makings of a complete album. Ashore is the happy outcome.

On the new release she takes the opportunity to revisit a couple of songs she has recorded before. It opens with ‘Finisterre’, a number that appeared on her 1989 collaboration with the Oysterband. The voice is close and intimate, the arrangement spacious. The track establishes a mood for what’s to follow. These are broad soundscapes opening onto long vistas, like a view of the open sea. Also up for reappraisal is Cyril Tawney’s ‘Grey Funnel Line’, which she first recorded with Maddy Prior in 1976 and has been singing on and off ever since. June still loves the duet version with Maddy but admits her own approach to the song has changed over the years: “It’s got a bit more space. It has room to breathe. The images, I think, stand out very clearly.”

With time, particularly if she hasn’t sung a song for a while and comes back to it, the meaning of the words changes: “That’s the beauty of a good song, that however well you think you know it, you discover something in it that you didn’t see before. Certainly, ‘Grey Funnel Line’ is a song that speaks so clearly – and I don’t know that I even thought about it when I first recorded it – of that need for anyone who has spent most of their life on the sea to turn their back on it. I’ve been told this by people who served for a long time in the Navy, that if you want a life of your own then you’ve got to leave the sea. And the more I sang it and thought about it, the clearer that became to me. That’s exactly what Cyril was writing about.”

One highlight of the London concert was a suite of songs about cannibalism at sea. This is a surprisingly virile genre, from the starkly lyric poetry of ‘The Ship in Distress’ to a comic treatment by Thackeray where the cabin boy’s on the menu until he’s rescued in the nick of time by the arrival of the fleet. On Ashore we hear a French song, ‘Le Petit Navire’, where the child is not so lucky. He ends up being eaten, with appropriate garnish. “I laughed so much when I found the words of that,” says June. “How French! They’d run out of anything to eat but they still managed to cook up white sauce and a nice salad! So I can only assume that ‘something to eat’ has got to mean meat!” The incidence of enforced cannibalism must be as old as seafaring, but, intriguingly, the songs about it only surface in the eighteenth century as broadsheets. The modern equivalent would be disaster movies about aircrash survivors. It all stems from our eternal love of horror, June suggests, lapsing into mock-Brummie: “As we say in the Midlands where I come from, ‘we loiks a bit of bad!’”

‘Le Petit Navire’ is one of two French songs on the new album collected in the Channel Islands. These were still being sung in the mid-twentieth century – the Islands remained French-speaking until the Second World War – and June is drawn to the way they combine a very English sensibility and loyalty to the English crown with their origins in the French tradition: “I love that – and also it gives me an excuse to sing in French!”

Like its predecessors, the album has a distinct aural texture. “We often get described as chamber folk. That’s a very good way of expressing that it isn’t quite folk music and it’s not classical and it’s a few other things as well.” June works with a regular group of co-musicians drawn from a variety of backgrounds. Huw Warren is a pianist and composer whose jazz-inflected style perfectly complements June’s vocals. “The piano is such a glorious instrument. It’s an orchestra in itself.” The multi-tasking Mark Emerson on violin and viola unites a classical training with a grounding in traditional and dance music. “Extraordinary player of an extraordinary instrument” is June’s comment on Andy Cutting: “Andy does things with the diatonic accordion that just aren’t possible to most other musicians.” The line-up is completed by Tim Harries on double bass, who, I’m told, has “two brains”.

How are the arrangements arrived at? “I come up with the songs and I have an idea of the direction I want them to go in and, quite possibly, an idea of what the main instrument should be as the basis of the arrangement. I learn the songs and I sing them to the musicians and we sit round and the arrangement evolves. It’s very much input from all of us as to how the finished arrangement ends up. Very seldom is anything written down. It’s carried in everybody’s heads. As far as I’m concerned the songs tell me what they need and I’m just trying to convey everything that I get from a song to a listener in the best way I can.”

As an example, she quotes the last track on the album, ‘Across The Wide Ocean’, an epic 12-minute setting of a Les Barker poem about the Highland Clearances. “The grounding of that song is piano and what Huw is playing. The musicians are improvising. They know roughly when each instrument should come in but they’re responding to the words and I just sing when I feel like it. It is a long track, it’s just the way we felt that the song deserved to be sung and played to give it that incredible breadth, so that it is a very visual arrangement. Through the music you see the sea, the people being driven from their homes, the dereliction of the island and the burning houses and the ships setting off for America. It’s all there in what the musicians are playing just as it is in the words. It’s one of those film songs – I like those.”

Despite her enviable technique, June insists she has no musical training. She seems apologetic that she can’t read music: “You’d think at my age I would have learned by now.” I point out that Paul McCartney has the same “disability” but has managed to do quite well for himself nonetheless – which seems to reassure her.

Martin Carthy always says that the worst thing you can do to folksong is not to sing it, and June agrees with him wholeheartedly. Does that mean she’s a curator? “I’m a teller of stories,” she responds. “I don’t like that word curator. It is part of what traditional music is about but it just seems to me the wrong word. I’m someone who is keeping great music alive. I’m a life-support machine rather than a curator.”

She first discovered folk music as a teenager. She recalls a couple of religious programmes on TV on a Sunday afternoon where folk artists like Martin Carthy were featured. When a schoolfriend took her to a folk club, she found a “social aspect, a way of life”. It was the start of her own involvement in singing, but the breakthrough moment was a chance purchase of Anne Briggs’s EP The Hazards Of Love.

“I went to visit my sister in London and she took me to Dobell’s, where they had jazz and folk sections in the basement, and I found that EP. I thought, this looks interesting. So I took it home and I put it on my funny little Dansette record player and I thought, God, this is amazing. Here’s a woman singing on her own, it’s just the voice. I want to do that. So I played it over and over again, I broke it down, slowed it down, cut it up into little pieces and learned how to do each little tiny bit, drove my mother mad, shut myself in the loo – there was a good acoustic in there! – and just taught myself how to sing like that. I was fascinated by the decorated style, the material.”

A late starter, she didn’t release her first album until 1976 and attributes the impetus to her old friend Maddy Prior. Steeleye Span were at the peak of their stadium-filling power in the mid-70s and their record company, Chrysalis, allowed each member to make a solo album. Maddy announced she would do hers with June, as a duo, the Silly Sisters. “So I actually stepped into a recording study. Oh God, how terrifying!” When she’d recovered from the fright, June got down to making the solo disc of her own that Topic had been pressing for, Airs And Graces. Since then she’s put out a string of accomplished releases, most of them bearing titles beginning with the letter ‘A’ (“It gives you somewhere to start when you’re looking for a title, which is not an easy thing to do.”)

Her background is somewhat different from many in the folk world. Oxford-educated, she captained her college team on University Challenge in 1968. They lost (narrowly) to Essex, despite “thumping” Bangor in the warm-up round. What sticks in the memory about that experience? “How nice Bamber Gascoigne was. And the other thing I remember, apart from not winning, is that we walked through the set of Coronation Street to get to the University Challenge studio. I got onto Coronation Street, albeit briefly!” Outside music, she’s served time as a librarian and even ran a restaurant in the Lake District for a while.

She is a remarkably versatile performer who can switch from trad folk to jazz by way of modern singer-songwriters. An earlier album, At The Wood’s Heart, brought a cool reading of Duke Ellington’s ‘Do Nothing Till You Hear From Me’. On the new album she tackles Elvis Costello’s ‘Shipbuilding’, already covered memorably by Robert Wyatt. Whatever the material, her singing has the naturalness of speech. Where lesser singers merely skate the surface, June is always deep inside the song.

She ducks when asked if she has any comments on the current folk scene. At first she admits she “hasn’t a clue”, then she speaks in praise of newcomer Emily Portman for “making new songs of old and working folktale and storytelling into songs” – which is, of course, exactly what June Tabor herself has been doing triumphantly for the last forty years.

[First published in Properganda 19, April/May 2011]